El Diamante

Well-structured and balanced, with a creamy body and honey sweetness. Apricot, cacao nibs and panela sugar.

This coffee was grown and processed by Neftalí Castro on his family’s farm, El Diamante (which translates to “the diamond” in Spanish), located near the town and municipality of Cajamarca, in the state of Tolima, Colombia. The 30 hectare property is owned and managed by Neftalí and his sisters, who are the third generation to run the farm.

When the farm was first established, the family planted plantain, green beans, potatoes and a local root vegetable called arrachacha. They also kept a small plot of Typica trees, but coffee was neither a priority nor an important source of income. This changed in 2008, when Neftalí, the youngest of the siblings, decided to return to his family farm and take over its management, after many years working as a mechanic in Tolima’s capital, Ibagué.

From the outset, his focus was on coffee production. During an inspiring visit to the renowned coffee producing region of Pitalito, Huila, he had recognised the potential of coffee and, from that moment, was determined to pursue the social benefits of the crop for himself and his family. Neftalí expanded the land dedicated to coffee by planting a further eight hectares of the Caturra variety. He established careful farming practices and built a small beneficio (wet mill) and drying sheds to process his crop. His efforts were rewarded when he placed 29th in 2009’s COE auction, then again in 2011 when he achieved an incredible 3rd place in the competition. This recognition also brought attention from local FNC technicians, who advised Neftalí to replace his Caturra trees with the higher yielding Castillo variety. Unfortunately, the variety did not perform well in such a cool climate, and what followed were a couple of difficult years for the farm.

Always enterprising, Neftalí made the hard decision to entirely replace the Castillo trees with the Tabi variety, a newer hybrid that is resistant to rust and performs well at higher elevations. This crop has been far more successful, and Neftalí is once again producing exceptional quality and good yields. Alongside some 9,000 Tabi trees, Neftalí has recently planted Caturra, Pink Bourbon, Gesha and Chiroso varieties, along with a mysterious tree he calls ‘Kenya Bourbon’ (also nicknamed the Ferrari because of its impressive potential) which Neftalí acquired from fellow producer Edward Sandoval, with the expectation that these lots will fetch higher premiums for their outstanding cup profile.

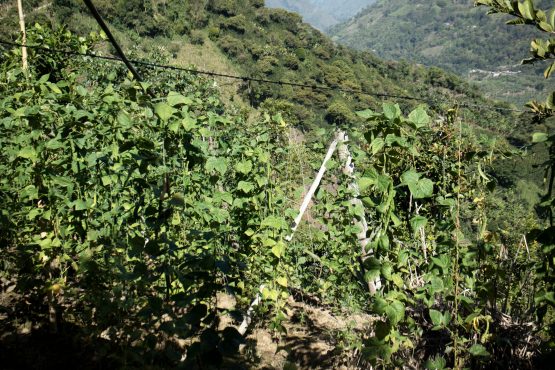

Although eight hectares of El Diamante are planted with coffee, the extremely steep incline of the land requires Neftalí to plant trees 2m x 2m apart, to ease access for harvesting and maintenance — taking the number of trees planted closer to what would traditionally be found on a five hectare plot. Coffee grows under the shade, including of guamo trees (a local variety of Inga that produces a very sweet fruit) that also provide home to many native animals like the guatín and lapa.

Neftalí is proactive and ingenious, and always has several projects on the go — whether that’s committing to helping neighbours improve their farms’ infrastructures, or investigating and trialing new coffee varieties on a plot he calls ‘La Locura,’ which translates to “the madness” in Spanish. This particular corner of the property includes all of the varieties grown at El Diamante and, along with the farm’s small wet mill, is Neftalí’s pride and joy.

Generous with his time and resources with fellow producers, Neftalí is considered a leader and role model within his town and a champion for coffee production. His resourcefulness, innovation and adaptability have helped him build El Diamante’s reputation for excellence and inspired many of his neighbours to focus on specialty production. As Neftali shares, “Coffee is my passion. I don’t want to do anything else.”

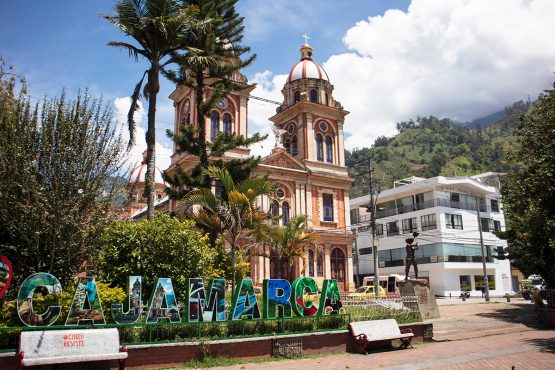

ABOUT CAJAMARCA

Cajamarca translates to ‘Cold Lands’ in the local Quechua language and was once a major settlement for the Anaime and Tochas indigenous groups, who put up over 70 years of resistance during the Spanish conquest of Tolima in the 16th century. The municipality was not established until 1867, when the remaining local communities were absorbed by Antioquean settlers whose realm of influence spread across western Colombia.

Historically, Cajamarca has been known as one of Colombia’s agricultural hubs. Thanks to nearby volcano Cerro Machín, the land is incredibly fertile, with volcanic soils rich in minerals and nutrients. The Anaime canyon below supplies the town with ample amounts of fresh water, and powers the the local fishing industry. Along with coffee, the municipality is known for being Colombia’s top producer of arracacha (also known as white carrot, or yellow cassava), a root vegetable that is rich in calcium and vitamin A and a staple of the local diet.

In recent years, the town has stood up to large mining companies that have been buying up land and destroying established farms in search for gold. The community has banded together and fought back, recognising that concentrating on agriculture is more environmentally and socially sustainable for their region long term.

Most farms in the region are planted with Caturra, which was the most popular variety during the 1970s and 1980s when the farms were established. Coffee in Cajamarca is farmed with traditional techniques. Fertilisation occurs around three times a year, usually after manual weeding, and pesticides are rarely used. The coffee is selectively hand-harvested, with most labour being provided by the farmers and their families.

ABOUT TOLIMA

The word ‘Tolima’ comes from the local indigenous language and means a “river of snow or cloud”. The region sits on the Cordillera Central, in the middle of the three mountain ranges that provide a range of microclimates well-suited to high-quality coffee production. Coffee is the leading agricultural activity in the region, followed by beans and cattle.

The most well-known regions in Tolima for specialty coffee are Planadas and Chaparral in the south. This coffee comes from the areas surrounding Ibagué, which is further north in the state. The city is also known as the “Ciudad del Abanico” or the “city of the folding fan” because when you look at it from the sky the rivers running from the mountains split up the crops of rice and cotton, and it looks like a beautiful handmade folding fan.

Coffee from Tolima has historically been very difficult to access due to the region’s isolation and instability. For many years this part of Colombia was under the control of Colombia’s notorious rebel group, the FARC, and as a result, it was unsafe and violent. Since 2012, safe access to this region has been possible as a result of peace talks between the Colombian government and the rebels. Since this time some stunning coffees from small producers have become accessible to the international market.

Our export partners for this coffee, Pergamino, have worked hard commercialise specialty-grade coffee throughout Tolima, and are now able to source some outstanding coffees from very dedicated producers. They work closely with the producers to give them feedback on their coffees (provided by Pergamino’s expert team of cuppers) and provide top up payments when the coffee is sold at a higher premium.

Head here to learn more about the work of Pergamino.

HOW THIS COFFEE WAS PROCESSED

The coffee in this lot were selectively hand-harvested, with most labour being provided by Neftali and his family. It was processed using the washed method at El Diamante’s ‘micro-beneficio’ (mill).

The freshly picked coffee cherries were pulped using a small manual pulper and then placed into a fermentation tank, for between 48-72 hours. Because of the cooler climate in Cajamarca, Neftali was able to blend two to three days’ worth of pickings to extend the coffee’s period of fermentation. Over that time, freshly picked cherry is pulped and added to the mix. This is key, as the fresh mucilage lowers the ferment tank’s pH level and – along with the cooler temperatures – allows for an extended fermentation process, which contributes to a vibrant, winey acidity in the coffee’s cup profile. The resulting parchment was then washed using clean water from nearby rivers and streams.

Once washed, the coffee was carefully dried (over 10–18 days) on parabolic beds, which are constructed a bit like a ‘hoop house’ greenhouse, and act to protect the coffee from the rain and prevent condensation dripping back onto the drying beans. The greenhouse is constructed out of plastic sheets and have adjustable walls to help with airflow, and temperature control to ensure the coffee can dry slowly and evenly.

The dry parchment was then delivered to Pergamino’s warehouse, where it was cupped and graded, and then rested in parchment until it was ready for export.