Kabumbu Estate AB

Rich and syrupy, with winey acidity. Raspberry and cherry, balanced by black tea on the finish.

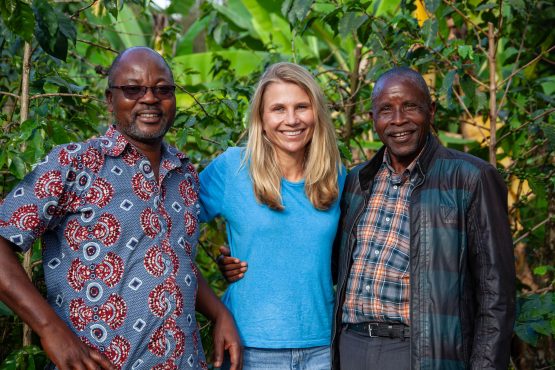

Kabumbu is a small, two hectare estate located in Kirinyaga County, owned and managed by Joseph Mugo Karaba and Pauline Mumbi Mugo (pictured above). The farm sits at 1,660 meters above sea level in the foothills of the extinct volcano, Mt Kenya, close to the Kamai river. The area is defined by its bright red, nutrient-rich, volcanic soil and cool climate, both of which contribute to the outstanding quality of the coffees produced on this farm. Joseph and Pauline grow tea and coffee across three acres, alongside other food crops like banana, macadamia and avocado.

Joseph and his brother inherited the shamba (Swahili for ‘farm’) from his father, who initially planted it with tea – a common crop in the high, cool hills of Kirinyaga. The brothers split the estate in half and each continued to farm tea on their separate plots until 2012, when Joseph and Pauline decided to try their luck at being coffee farmers. The couple planted half an acre of coffee trees alongside their tea shrubs, and today they produce around 200kg of green coffee annually.

Most of the coffee Joseph and Pauline grow is the Batian variety, a high-yielding and disease resistant hybrid that performs well in Kirinyaga’s cooler climate. When they first planned their coffee production, Joseph made the unusual choice to plant 100% Batian (in a region known for producing SL28 and SL34 varieties) – recognising that it made the most sense long term to invest in a stronger and higher yielding crop. Besides its physical attributes, Batian produces excellent cup quality, allowing Joseph and Pauline to maximise the potential of their land and make good profits from their coffee.

Recently, Joseph has further invested in the shamba by planting SL28 and SL34 varieties that have been grafted onto Ruiru 11 rootstock. During our most recent visit, he pointed out that the hardier rootstock is better for the cooler climate and prolonged dry period experienced in Central Kenya.

Joseph is a charming, thoughtful and progressive man, especially when it comes to his farm and industry. Beyond the work he has done at his estate, he is the leader of the local Kirinyaga Arabica AA farmers group, with a total of 50 members who work together to support and provide resources to each other throughout the year. He is also a chairman at his church, while Pauline a nurse by practice who also sells vegetables and cereals from their farm at the local market.

“Life is difficult when you make it difficult. Life is good when you share what you have and what you know”

Joseph Mugo Karaba

In 2016, Joseph built a small wet mill – or factory, as they are called in Kenya – on his land. This facility enables Joseph to process and dry his crop onsite, rather than selling fresh, whole cherry to the local Farmers’ Society Cooperative. By processing his coffee independently, Joseph is able to control every step of the coffee’s production directly – from farming, to harvesting, processing, drying and sale – ensuring the full potential of his crop is achieved in terms of quality and sale price. The resulting coffee lots reflect the incredible amount of hard work and attention to managing every single variable that influences quality.

Choosing to process the coffee independently is not easy—or cheap. Managing processing on such a small scale has required significant investment in infrastructure, equipment and staff. It is also far costlier to mill and market small volume lots than large day lots. This investment has paid off, however, as Kabumbu is now producing some exceptionally high-quality lots which fetch very high prices at the point of sale. It also allows Joseph and Pauline to employ around 20 workers from nearby communities during the peak of the harvest. As Joseph states: “We love when people like MCM end up taking our coffee. I feel pride when people like you take my coffee, because I really feel like I receive payment for my work. When I get something good from you, it helps us improve our house, and the lives of our kids.”

Since the Kenyan government’s coffee trade reforms of 2023, we have been sourcing Joseph’s coffee directly, with the help of Wycliffe Murwayi as the marketing agent. To secure direct sales, Joseph has opened a USD account and is now responsible for producing the required documentation for export. The benefits of the direct model are higher profits, as the buyer (in this case, MCM) must offer competitive pricing to secure the coffee, and a faster turnaround time between the sale and the grower receiving their payments. Direct sales also support a more meaningful and values-led relationship between the growers and their buyers and have become more widespread as the coffee sector adapts to the reforms.

ABOUT KIRINYAGA

Kirinyaga County is part of Kenya’s former Central Province, which was dissolved in 2013. The area includes Murang’a, Nyeri, Kirinyaga, Kiambu and Nyandarua Counties, and is traditionally the homeland of people of Kikiyu ethnicity. The central highlands of Kenya are considered to be one of the wealthiest areas of the country, due to the incredibly fertile land, geographical proximity to the capital, Nairobi, and close integration with the country’s colonial administration before Kenya gained independence in 1962. This integration afforded the communities of Central Kenya with opportunities for education, business and political prowess, despite the various injustices of the colonial government. The Kikiyu people have a long and proud history of agriculture and the region is farmed intensively, with coffee, tea and dairy being the most important modern crops.

Like Joseph, many of the producers in the region are second-generation landholders, whose parents purchased and planted the land in the 1950s and 1960s, after agricultural reform allowed for small Kenyan farmers to produce cash crops on their family farms (instead of only on large, British owned estates). Farmers in Kirinyaga grow coffee as a cash crop alongside food crops like banana, maize, macadamia, avocados and vegetables. Tea and dairy are also important sources of income for the producers.

GRADING

Kenya uses a grading system for all its exportable coffee lots. The grading system is based on the size and assumed quality of the bean. A coffee’s grade is directly correlated with the price it attracts at auction or through direct trade.

This coffee is AB grade. This grade is easily defined by size (in this case, AB means that the beans are screen size 15 and above) and to a certain extent, quality. While it is assumed that AA lots represent the highest quality, we have often found AB and peaberry lots to be just as good.

HOW THIS COFFEE WAS PROCESSED

The coffee was carefully handpicked by Joseph and his team of around 20 seasonal workers. During the peak of the harvest, cherries are picked every two weeks, to ensure they have adequate time to ripen between passes. To avoid over-picking, pickers are paid on a daily rate rather than by weight.

After sorting, the ripe, red cherry was pulped using a pulping machine, which removes the skin and fruit from the inner parchment layer that protects the green coffee bean.

The coffee was then dry fermented for 12-24 hours, to break down the sugars and remove the mucilage (sticky fruit covering) from the outside of the beans. Whilst the coffee was fermenting it was checked frequently, and when ready it was rinsed and removed from the tanks.

Using clean water from the nearby Kamai River, the parchment-covered coffee was then washed and graded in water channels, before being transferred to raised drying tables (also known as African Beds). During the drying stage, which takes up to three weeks, the drying parchment was turned constantly to ensure it is dried evenly, until it reached 11–12% humidity.

Once ready, coffee transported to the Embu County Mill to be dry milled and prepared for shipping.

WHAT’S IN A NAME

Kabumbu (pronounced “kah-boom-buh”) means “small hill, or ant hill” in Swahili. It is the name of a micro-region in Kirinyaga, and of a church near Joseph’s farm.