Kiangundo AB

Pink Lady apple, cherry and honeyblossom, with sugarcane sweetness. Well-structured and juicy.

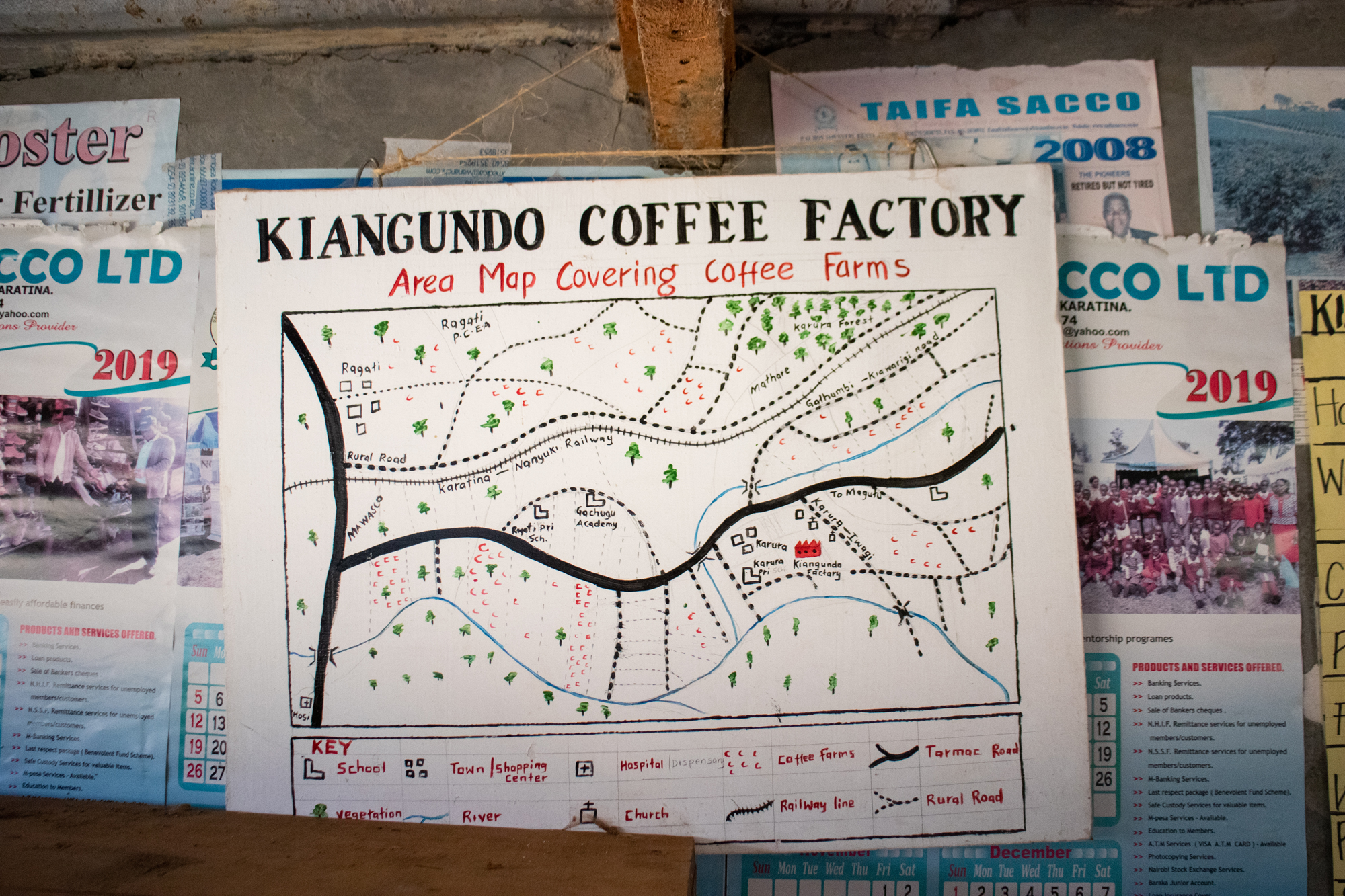

Kiangundo is a washing station located on the slopes of Mount Kenya, in the Karatina Municipality of Kenya’s Nyeri County. Established in 1968, it is one of four washing stations (or factories, as they are called in Kenya) owned by the Kiama Farmers’ Cooperative Society (FCS).

Kiangundo receives coffee cherries from some 800 of the cooperative’s members (50% male, 30% women and 20% youth) who have small farms sitting on the foothills of the extinct volcano at 1700-1800m above sea level. This area is defined by its bright red, nutrient rich volcanic soil and this combined with the regions cool climate and high elevations contributes to the outstanding quality of coffee produced here.

The land that surrounds Kiangundo is also rich is biodiversity. Close to the factory lies the large Ragati Conservancy, a large 8,000 hectare protected area that consists of montane forest and marshes and is home to an abundance of wildlife including elephants, buffalo and leopards.

Manager Jackson Mahu Kooro, who originally joined Kiama in 1999, oversees the collection and careful processing of the coffee cherries following a promotion to factory manager in 2022, after 17 years as as Kiangundo’s machine operator. Besides Jackson, Kiangundo employs five permanent staff members year-round and an additional twenty workers during the season.

As part of their commitment to excellent quality, the cooperative has made several investments in the Kiangundo washing station in recent years. In 2020, the cooperative upgraded to digital scales, providing farmers and clerks with better accountability when coffee cherry is delivered. The factory is also in the process of completing their Rainforest Alliance certification, as part of Kiama’s commitment to social, economic and environmental sustainability. Since 2023, the processing centre has distributed shade tree seedlings to its members, all grown on a nursery they have built onsite.

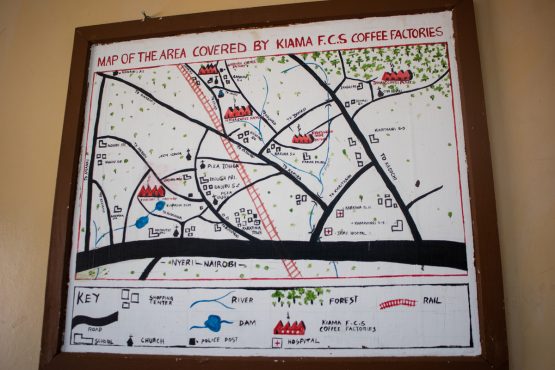

ABOUT KIAMA FARMERS’ COOPERATIVE SOCIETY

Kiama FCS was formed in 2005 when two existing cooperatives merged into one. Today they own four washing stations in Nyeri (Gachuiro, Kiangundo, Ichuga and Kiamaina), and a cherry collection point, Inwagi. In total, over 3,000 Nyeri farmers are members of the cooperative. Most own small shambas (Swahili for ‘farm’) averaging just half a hectare in size, and grow coffee alongside other food crops like banana, maize, macadamia, avocados and vegetables. Tea and dairy are also important sources of income for the producers in this region.

Kiama supports its farmer members by offering pre-harvest financing, allowing them to plan and invest in the upcoming crop. They also buy inputs in bulk and distribute them to members at a lower cost than otherwise possible and advise on the best timing of application. By providing farmers with strong agricultural support and reliable price premiums, Kiama’s membership has grown by over 20% since 2022 and volumes have doubled.

Kiama has six elected board members, who are all members of the cooperative. Board members are re-elected every three years (to avoid corruption), must be active farmers and must attend monthly trainings. The current chairman, Charles Ndamburi Nguve has led the board for 11 years, and is supported by by CEO and Secretary Manager Iddah Rose Wangui Kigathu. The cooperative currently employs 24 permanent staff members, who work out of their office in the town of Baricho, some 130km north of Nairobi.

Since the Kenyan government’s industry reforms in 2023, Kiama has connected more closely with coffee buyers by selling a small percentage of their production through direct sales, rather than through the auction. In this model, price negotiations are done directly between the grower (in this case, Kiama FCS, representing their farmer members) and the buyer (in this case, MCM). To facilitate direct sales, Kiama opened a USD account and are now responsible for producing the required documentation for export. The benefit of this model are higher profits, as the buyer must offer competitive pricing to secure the coffee, and a faster turnaround time between the sale and the grower receiving their payments. Direct sales also support a more stable, meaningful and values-led relationship between the growers and their buyers and have become more widespread as the coffee sector adapts to the reforms.

ABOUT NYERI

Nyeri County is part of Kenya’s former Central Province, which was dissolved in 2013. The area includes Murang’a, Nyeri, Kirinyaga, Kiambu and Nyandarua Counties, and is the traditional homeland of the Kikiyu people. Historically, Kenya’s central highlands are some of the wealthiest areas of the country, due to the incredibly fertile land, geographical proximity to the capital, Nairobi, and close integration with the country’s colonial administration before Kenya gained independence in 1962. This integration afforded the communities of Central Kenya with opportunities for education, business and political prowess, despite the various injustices of the colonial government. The Kikiyu people have a long and proud history of agriculture and the region is farmed intensively, with coffee, tea and dairy being the most important modern crops.

Many of the producers in Nyeri are second-generation landholders. Most of the coffee in the region was originally planted in the 1950s, after agricultural reform allowed for Kenyan nationals to produce cash crops on their small family run farms (instead of only on large, British owned estates). At that time, it was recommended to plant SL28 and SL34, which remain the predominant varieties found in the area. Both cultivars have Bourbon and Moka heritage and are named after the laboratory that promoted their wider distribution in Kenya during the early 20th Century: Scott Laboratories. This lot also contains a small percentage of the hybrid varieties Ruiru 11 and Batian, which were cultivated as more robust varieties, with better resistance to Coffee Berry Disease and Coffee Leaf Rust. Both varieties have been backcrossed with SL28 and SL34 to achieve a high cup quality.

GRADING

Kenya uses a grading system for all its exportable coffee lots. The grading system is based on the size and assumed quality of the bean. A coffee’s grade is directly correlated with the price it attracts at auction or through direct trade.

This coffee is AB grade. This grade is easily defined by size (in this case, AB means that the beans are screen size 15 and above) and to a certain extent, quality. While it is assumed that AA lots represent the highest quality, we have often found AB and PB lots to be as good, if not better.

HOW THIS LOT WAS PROCESSED

All the coffee cherry is hand-picked and delivered on the same day to the washing station, where it undergoes meticulous sorting. This is also done by hand and is overseen by a ‘cherry clerk’ who ensures any unripe and damaged cherries are removed. The ripe cherry is then digitally weighed and recorded, and the farmer receives a receipt of delivery.

The coffee is then placed in a receiving tank and pulped using a four-disc pulping machine to remove the skin and fruit from the inner parchment layer that protects the green coffee bean. After being pulped, the coffee is sorted by weight using water, with the highest quality and densest beans being separated out from the lighter, lower-quality beans.

The coffee is then dry fermented for 20–24 hours, to break down the sugars and remove the mucilage (sticky fruit covering) from the outside of the beans. Whilst the coffee is fermenting it is checked intermittently and when it is ready it is rinsed and removed from the tanks and placed in a washing channel.

The parchment-covered coffee is then washed with fresh water from the nearby Ragati River and sent through water channels for grading by weight. The heavier coffee, which sinks, is considered the higher quality, sweeter coffee, and any lighter density or lower grade coffee beans are removed. The beans are then sent to soaking tanks where they sit underwater for a further 24 hours. This process increases the proteins and amino acids, which in turn heightens the complexity of the acidity.

After soaking, the coffee is pumped onto deep drying beds where they drain for 1-2 hours, before being transferred to raised drying tables (also known as African beds). As they dry the parchment is turned constantly to ensure even drying, and so that any defective beans can be identified removed. Time on the drying tables depends on the weather, ambient temperature and processing volume: taking anywhere from one to three weeks to get to the target moisture of 11–12%. After drying the coffee is moved to conditioning beds, where it rests in parchment for about a month. This resting period helps to stabilise water activity and contributes to long-lasting quality and vibrancy in the cup.