El Faldón

Intensely sweet, with winey acidity and fruit forward character. Blueberry, plum, and starfruit, with black tea on the finish.

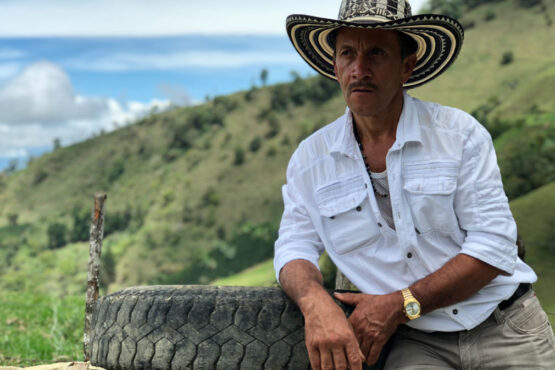

This microlot was produced by Rubén Darío Gómez and wife Rosa Eleny (pictured below), on their two hectare farm, El Faldón (which translates to “the big skirt or slope” in Spanish), located near the small community of La Noque, in the municipality of Caicedo, in Colombia’s Antioquia state.

Don Rubén embodies the hard-working, intrepid character of an Antioquian coffee producer. Born and raised in the remote hills of Caicedo, Rubén wasn’t able to complete his schooling and did not inherit land or assets from his family. At a young age, he began working as a coffee picker, travelling across the state as the crop came into season in different areas. He worked for over a decade as a migratory farm worker, and still has strong memories of the many cold nights he spent sleeping in burlap sacks in old sheds. Over the years, he persevered with his dream to one day own a coffee farm, saving as much as possible to be able to buy his own parcel of land.

Eventually, Don Rubén saved enough money to purchase two hectares of land in the higher areas of Caicedo, some 2,100 meters above sea level. The property originally belonged to colleagues of his who moved to Antioquia’s capital of Medellín, and allowed Rubén to establish a payment plan to be able to make the purchase. Land was more affordable in this area, as the high elevations and cool temperatures were deemed unsuitable for coffee production. Many of his friends and family warned him against establishing a farm here but, as Rubén recalls with a laugh, “I really had no choice,” since it was the only land he could afford.

After some early years with low yields, Rubén Darío’s persistence and hard work paid off, with El Faldón’s production rising year on year. The cool climate and high elevation of La Noque contribute to the outstanding cup profile produced at the farm, which Rubén first discovered when receiving feedback and performing well at local specialty coffee competitions. Since then, he has partnered with our Colombian supply partner, Pergamino, who connect him to specialty coffee buyers like MCM and help him access high premiums for his coffee lots.

Over his entire time at El Faldón, Don Rubén has committed himself to investing in his farm and on finding ways to improve the region’s infrastructure to better support the 18 other families who farm coffee there. Through enormous amounts of hard work and clever thinking, he has been able to achieve this goal in significant ways. Because most of the families of La Noque grow coffee on very steep terrain, for decades they have had to walk down a dangerous path, loaded with cherry, and then back up to reach their homesteads to process their crop. In 2020, Don Rubén invested in building a pipe that extends across the divide that separates farmlands from the community (that’s approximately one kilometre of tubing!), to make the cherry delivery process more streamlined. The process starts at a tank built at the top of the mail hill, where fruit is placed and pushed down the tube using water and gravity, until it reaches the other side, near Rubén’s house, saving the community hours of labour and creating a safer environment for seasonal staff to work in. Additionally, Don Rubén has spent the last ten years building a road that connects the main road that leads to town, using his own funds and working with Pergamino and the local mayor to support the project. Costing some $15,000 to build, the road has been transformative for the community, and is a great source of pride for Rubén.

El Faldón is mostly planted with the Caturra variety but including a few older Bourbon plants that were already established when Rubén purchased the land. All farming follows traditional techniques and most of the labour is provided by Don Rubén and his family, with two to three seasonal workers lending a hand during the peak of the harvest. Fertilisation occurs around three times a year, usually after manual weeding, and pesticides are rarely used.

On our most recent visit, we asked Don Rubén what he hoped for his and his family’s future at El Faldón, which he told us was “to continue expanding the amount of coffee we grow, because that generates us a better income. We want to grow even more coffee!” Having already made vast improvements to the farm’s infrastructure, Rubén wants to use that income to purchase a truck, “to be able to carry parchment down the hill on my own vehicle and deliver it to Medellín myself.” Given how far he’s come, if the climate allows it, we’re convinced he’ll be able to do this in no time!

ABOUT CAICEDO

Caicedo is one of the highest coffee-producing regions of Antioquia, and therefore in Colombia. Coffee is grown on the side of deep canyons, dropping down to the mighty Cauca River, some 500m above sea level. The steep canyon walls trap warm currents, which circulate to higher ground and make it possible for coffee to be grown at such staggeringly high elevations. The unique geological attributes of the region contribute to the outstanding cup profile of coffees farmed and processed in the area. Typically, farms in the area are very small – on average just 2 hectares in size- and are farmed traditionally, with most of the labour being provided by the family.

Smallholder farmers in the highest areas of Caicedo, like La Noque, were pioneers in planting and producing coffee at these high elevations. They were initially told by Colombia’s national coffee grower’s federation (Federacion Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia or FNC) that it would be impossible to grow coffee in such a cool climate. However, many farmers bought land here out of necessity as it was much more affordable than at lower elevations, which were considered more prosperous for coffee production. Now, the area has become recognised for the exceptional cup quality and characteristics. The cool climate is ideal for the slow ripening of coffee cherries, leading to denser beans and a sweeter, more complex cup profile. Coffees from La Noque now attract high premiums from specialty buyers, who are able to access the region through the work of exporters like our supply partners, Pergamino.

During the 1990s, Caicedo experienced some of the highest levels of FARC-led violence in Antioquia. Coffee growers were especially targeted: their crop was often stolen, and farmers were extorted or kidnapped by the armed guerrilla forces. In the early 2000s, as the population became increasingly exasperated, nonviolent marches began to be organised, often alongside trucks loaded with coffee making their way to state capital Medellín.

These signs of protest offered coffee growers some level of protection, though the violence did not abate entirely. After an especially grim aggression against Antioquia’s state governor, the people of Caicedo came together in even greater numbers, to protest peacefully against the guerrillas. The municipality went on to become Colombia’s first official Nonviolent municipality, and today remains one of the regions with the lowest homicide rates in the country.

ABOUT ANTIOQUIA

Antioquia is located in central northwestern Colombia. Coffee was introduced to the region in the latter part of the 19thcentury. Since then, this mountainous, fertile department has 128,000 hectares of coffee that is produced by a mix of large estates and tiny farms.

Antioquia only recently became more accessible to specialty coffee buyers – largely thanks to a transformation of the department led by Sergio Fajardo, who was the governor of the department between 2012-2016. Sergio transformed Antioquia’s capital city, Medellín, from a violent and dangerous place to a world-class tourist destination with a strong economy. Coffee has played a significant role in this transformation, and as access to many producers has improved, the region has become one of Colombia’s most important and celebrated coffee-producing areas.

Our export partners for this coffee, Pergamino, have worked hard commercialise specialty-grade coffee throughout Antioquia, and have uncovered some stunning coffees and very dedicated producers in the process. They work closely with the producers to give them feedback on their coffees (provided by Pergamino’s expert team of cuppers) and provide top up payments when the coffee is sold at a higher premium.

Head here to learn more about the work of Pergamino’s work in Colombia.

HOW THIS COFFEE WAS PROCESSED

This lot was selectively hand-harvested, with most labour being provided by the Rubén and his family. The coffee was processed using the washed method the farm’s ‘micro-beneficio’ (mill).

The coffee was pulped using a small pulper, and then placed into a tiled fermentation tank. Because of the cooler climate in Caicedo, producers tend to ferment the coffees for longer than usual and will often blend several days’ worth of pickings over a 3-5 day period. Every day, freshly picked cherry is pulped and added to the mix. This is key, as it lowers the pH level and – along with the cooler temperatures – allows for an extended fermentation process. This fermentation process contributes to a vibrant, winey acidity in the coffee’s cup profile. Parchment was then washed using cold, clean water from the nearby Bocachica river.

It was then carefully dried (over 10–18 days) on parabolic beds, which are constructed a bit like a ‘hoop house’ greenhouse, and act to protect the coffee from the rain and prevent condensation dripping back onto the drying beans. The greenhouse is constructed out of plastic sheets and have adjustable walls to help with airflow, and temperature control to ensure the coffee can dry slowly and evenly.

Once dry, the coffee was delivered to Pergamino’s warehouse, where it was cupped and graded, and then rested in parchment until it was ready for export.