Sítio Capão

Crisp and refined, with great structure. Orange blossom, pomegranate and roasted hazelnut.

Sítio Capão is a beautiful 16 hectare coffee farm owned by third-generation farmer Aneilson Souza and wife Rosemeire, who live on the property with their three children. Aneilson is hardworking, ambitious and motivated, having already accumulated over two decades of experience in coffee — even if he’s still in his early 40s! From the moment he took over the farm’s operations, Aneilson had a clear vision and understanding of its potential to produce extraordinary coffee.

Sítio Capão was originally established some 70 years ago as a fruit and vegetable plantation by Aneilson’s grandfather. This was well before modern coffee varieties and practices were introduced to Brazil, and the coffee industry was only just becoming established in the region. At the time, coffee grown in Piatã was still being transported on donkey carts to be sold at local markets in nearby towns. When Aneilson’s dad took over operations, he planted the first coffee trees in an attempt to capitalise on the growing industry. Ultimately, however, the family did not find much success and were unable to keep up with how quickly the local market’s demands were changing.

At just seventeen years of age, Aneilson realised they needed to overhaul their approach to agriculture and coffee production to make a success out of Sítio Capão. With this in mind, he began his studies to become an agricultural technician at Bahia’s Federal Institute (IFBA). During this time, Aneilson stayed connected to the farm by visiting it every six months. Every time he returned home, he brought back more of the knowledge he was gaining at IFBA, and he shared it with his parents to try to help them improve their farming practices. Being apart from his family was a challenge — and Aneilson still gets emotional when recounting the experience — but his time away from Piatã cemented his intentions of returning to live and farm in his hometown.

Upon graduating, Aneilson returned to Capão, with the intention of fully realising the estate’s potential. A chance meeting with Silvio Leite, who had already made a name for himself as one of the founders of the Cup of Excellence, is what inspired him to focus on coffee. He started by replanting the farm with modern varieties like Catuaí, Catucaí 2SL and Catucaí 785 — all chosen due to their high productivity and cup quality, resistance to pesst and disease and, importantly, their suitability to Brazil’s climate.

In 2009, Aneilson began to work as an agronomist at a large vegetable company near the town of Mucugê (close to Fazenda Progresso) where he further expanded his knowledge of good agricultural practices. “Working at a larger scale operation was life changing in many ways,” he explained to us, “I learnt a lot”. Throughout this time, Aneilson continued to look after Capaõ on the weekends because, as he put it, “All my dreaming was here. I was always thinking about my farm. It was a seed in my heart and it kept growing over this time.”

Using the knowledge he gained through his studies and working as an argronomist, Aneilson began analysing the property’s soil, and preparing fertislisers (using a mix of organic and synthetic materials) to feed his trees, designing them to target any deficiencies present. He also introduced shade trees to his estate to block the wind, protect coffee trees from the sun’s full intensity, and improve the farm’s biodiversity, and intercropped the estate with nutrient-rich crops like cauliflower, broccoli and fruit trees to further nurture the soil.

In 2014, electricity was finally installed at the property and it was this point that Aneilson decided to quit his job as an agronomist to focus on Sítio Capão full-time. Whilst this felt like a big leap at the time, he has not looked back. “It was the correct decision,” he asserted when we last visited him. In the decade that’s followed, Aneilson has steadily invested in Capão. “Every year we dream, and then we make changes,” he told us. Using money saved from his time working as an agronomist he installed a generator at his wet mill to help mechanise the pulping of his coffee, built fermentation tanks, set up a drying patio and greenhouse to improve the quality of his processing, and established a water reserve. Most recently, Aneilson has installed solar panels at the property, and upgraded the drying patios.

In addition to tending to his farm, Aneilson roasts his own coffees on a Brazilian-made 15kg Ruralmac. Every weekend he sells his beans at a local market along with other produce from his farm including strawberries, kale, broccoli and cauliflower. His roasting enterprise has grown to become a co-roasting space for other coffee professionals and cafés in the region.

When we asked Aneilson what he’d like the to tell Australian community drinking his coffee, he told us, “I ask each Australian to enjoy a cup of coffee from Capão. This coffee arrived there, with a lot of love and dedication, from the residence of a young man with a lot of dreams about coffee, who dedicated his entire life to this moment. Each dose of coffee is brought to you by this dream, which today has a family involved. This dream will maintain the story with the new generation, which are my children. Together, we will be stronger.”

ABOUT PIATÃ

Located at the foot of the Chapada Diamantina mountain range, Piatã is a unique growing region in Brazil’s Bahia state. The coffees produced here tend to be floral, sweet and complex, and noticeably distinct from those grown elsewhere in the country. There are two main factors behind this: coffee grows at elevations of up to 1,400 meters above sea level, which is high for Brazil; and temperatures range from about 2°C to 18°C in winter, some of the country’s lowest. Combined, the high elevation and cool climate are key in slowing down the maturation of the coffee cherries, leading to an increased concentration of sugars in the bean. The result is a cup profile that is bright, transparent, and distinctive. Piatã’s relative proximity to the Equator line ensures the region’s coffee trees can experience such drastic conditions without being affected by frost, unlike other, more traditional growing regions like Minas Gerais.

Piatã’s exceptional natural characteristics also contribute greatly to the coffees’ profile. In the distant past, the whole of Chapada Diamantina was completely under water, slowly eroding over millions of years — leaving behind soil that is nutrient-rich and slightly soft. This soil, along with the above-average local humidity, is home to a healthy and diverse ecosystem that includes some 1,600 individual plant species. While the highlands of Chapada are rugged and dry, the area surrounding Piatã is filled with streams, waterfalls and even swamps that, in most years, provide plenty of water for irrigation and agriculture.

While coffee production is on the rise in Piatã, it is still very much a developing industry. Locally produced lots didn’t gain recognition for quality among Brazilian buyers until the 1990s. This recognition led to the establishing of the ASCAMP growers’ association in 1998, which was tasked with assisting growers who had land, but few resources. Over the next decade, cooperatives and other farmer groups were founded, playing a pivotal role in elevating the coffees grown and processed in the region. Piatã went on to be internationally recognised for its high quality in 2009, when five of the top 10 spots in Brazil’s Cup of Excellence came from this small corner of Bahia. The region’s dominance in the competition has continued every year since, particularly in 2016 when an astounding 19 of the 24 winning lots came from Piatã, and again in 2022, when 10 local winners were recognised. MCM has been sourcing coffee from this region since 2015, thanks to the support of longtime partner and coffee mentor Silvio Leite. Head here for more on Silvio and the incredible work he’s done in Brazil.

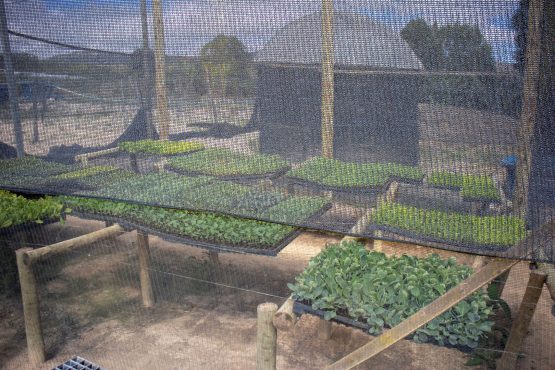

Part of what makes the Piatã region so special is that production is extremely limited, given the scale of the local estates. Farm sizes tend to be relatively small when compared to other producing areas in Brazil, usually just ten hectares or less in size, and are not visible when driving through the outskirts of town (unlike somewhere like Cerrado de Minas in Minas Gerais, where large estates make up the majority of the landscape). Most growers process their own cherries on site, sticking to traditional methods with little focus on experimentation, as the goal is to process coffee well to ensure the final cup is sweet and clean. Because many producers rely on coffee as their main source of income, simplicity and repeatability are prioritised. Great attention to detail is placed on the post-harvest work, as the region’s cooler temperatures and high humidity pose risks to the drying parchment. To prevent any potential defects in the cup, many local producers have built greenhouses and raised beds, to add a layer of protection without minimising the necessary ventilation for coffee to dry evenly and at a steady rate.

The region of Piatã is the traditional home of the Cariri and Maracá indigenous people, who were defeated during the Portuguese invasion of Brazil in the seventeenth century. While most of the remaining Cariri people were displaced to other regions within the state of Bahia, eventually joining other indigenous communities, the Maracás have a nearby municipality named in their honour, as it is located on their historical capital city. The word “piatã” translates to “hard foot or fortress” in the indigenous Tupi language (which was spoken by most First Nations People along Brazil’s coast). Head here to learn more about beautiful Piatã.

HOW THIS COFFEE WAS PROCESSED

Aneilson takes great pride and care in the way that he harvests and processes his coffee, from the preparation of the land through to the final storage of parchment. During harvest, all cherries were picked by hand only when fully ripe, with most of the labour being provided by him, his family and a handful of neighbours and seasonal workers. During the harvest, the team transport the freshly selected cherries in baskets to be depulped twice a day at Sítio Capão’s small wet mill. By doing all of the wet processing onsite, Aneilson retains full autonomy over how each coffee lot is treated, ensuring the highest quality is achieved and reducing overall operating costs.

After depulping, wet parchment with some mucilage still attached was sun-dried on patio for a week, followed by another week where it dried on patio during the day and in greenhouses overnight. Aneilson and his team spread the coffee in layers of about four centimetres and raked about 20 times a day. Once the coffee reached its optimal moisture content, it was separated into numbered lots and dry milled at the nearby Fazenda Machado, which belongs to Mr. Agnon Arauj0, a friend of Aneilson’s. It was then stored and rested at one of Fazenda Progresso‘s purpose-built warehouses, where it was prepared for export.