La Luna Dry Mill

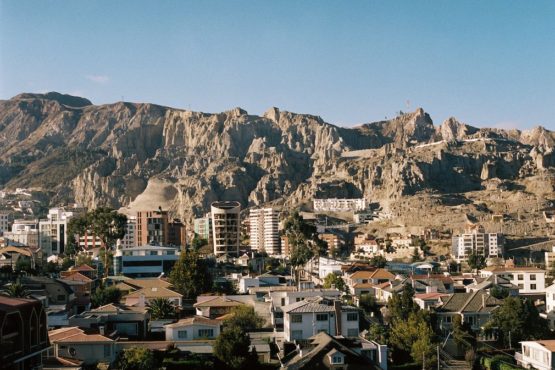

Agricafe’s dry mill, La Luna, is located in Kañuma, a neighborhood of La Paz about 15km from the city centre. The mill sits at a staggering 3,800m above sea level, making it one of the highest (if not the highest!) dry mills in the world.

La Luna is strategically located to access the main route to the port, without having to pass through the busy city below. The road to reach the mill are steep and a little dangerous, with deep gutters and sharp corners. Along the way, there are many street vendors, who sell everything from small individual candy, to bags of peanuts, and plastic bags of fresh fruit juice. There are also many vendors selling building supplies to support the rapid growth that the towns of El Alto and La Paz are currently experiencing.

The mill itself has spectacular views of the surrounding region. La Paz sits in a valley formed by volcanic activity (despite being at 3,600m above sea level), surrounded on one side by the vast tablelands of the Altiplano Plateau and the other side by the Cordillera Real, a mountain range that sits between La Paz and the Amazon basin where the coffee is grown. Both La Paz and La Luna sit above the tree line, so there is very little greenery nearby. Walking up to La Luna truly makes you feel like you have arrived on the Moon.

The mill’s premises, as well as most of the processing equipment inside, are kept in pristine condition. The building also houses Agricafe’s export offices, and includes a cupping lab and meeting room, both with wonderful views. A total of 20 permanent staff run La Luna year-round. Operations at La Luna have been managed by Efraín Arrata since the mill was first established in 2012. Previously, Efraín was responsible for overseeing the warehousing of Agricafe’s parchment with a third party supplier. A natural problem-solver, Efraín shared that he is motivated by challenges that arise during the harvest, and enjoys working at La Luna because it allows him to “contribute to a high quality, competitive product.” In this, he is assisted by Victoria Durán, known affectionately as Vicky, who serves as the mill’s QC manager. Durán started working at the dry mill in 2014, and has been roasting and evaluating lots since 2018.

During the peak of the season, the mill receives up to three truckloads of coffee parchment or pods per week, which reduces to one per week during quieter periods. The site processes around six tonnes of parchment per day — though the equipment has capacity for more volume, Efraín chooses to slow things down to make sure that his team has the time and attention to employ best practices, ensuring Agricafe’s high quality expectations are met.

HOW THE COFFEE IS PROCESSED:

Coffee arrives having already been tagged and labeled at the wet mill. To ensure traceability is maintained at every step of the way, each individual lot is identified by the same code it receives at the point of cherry delivery all the way through to export.

On arrival, lot details are checked to ensure they correspond with the lot they are expecting, before the parchment is weighed and its moisture percentage checked and recorded. The parchment is then loaded into the first screening machine, which essentially ‘cleans’ the coffee by removing all sticks, stones and remaining foreign matter. This machine has two large vibrating screens: the first only allows coffee parchment to fall through (up to screen size 25), effectively sorting everything larger than the seeds out. The second screen sits below the first one, and removes everything that is smaller than coffee seeds (down to screen size 14), allowing no dirt or stones to filter through. In the second stage, the coffee is hulled in a machine made by Pacific, which uses friction to loosen the parchment off the seeds.

Once the coffee is hulled, it undergoes additional sorting to ensure a consistent product. In the third stage, the milled green coffee is sorted by size. Efraín’s team use the same screening machine that starts the milling process, but this time the screen sizes are much more finely tuned, allowing only coffee that is between size 14 and 18 to pass through to the next stage.

In the fourth stage, the coffee is sorted by density by using a vibrating table that separates lighter seeds (unripes, etc.) from more dense seeds. From this stage the rejected beans or “seconds”, go through a second density sorting machine that recovers any dense, or “firsts”, and feeds them back to the main lot.

In the fifth stage the coffee passes through an electronic laser colour sorting machine. This is a 15 channel machine, which rapidly takes a photos of each individual seed that streams channel, and rejects those that don’t meet a set of pre-determined parameters. The machine can be fine tuned to specification, and can reject anything from full black and sour beans to seeds that fall just slightly outside of the specified colour range. These colour sorting machines are extremely efficient and contribute to exceptional quality.

The final stages of sorting are done by hand — as Efraín tells us: “no machine is as good as the human eye.” The mill employs 8-10 seasonal workers to hand pick over the coffee as it passes by on conveyor belts. The first round is done in a dark room, lit only by an ultraviolet light, which highlights any seeds affected by defects like higher moisture content, mould and bacteria, or chip marks from the de-hulling machine. Once the coffee has gone through the UV sorting, it then passes through a second round of sorting under natural light.

The prepared lots are then cupped and assessed, and depending on results, either sent back to be re-sorted, or placed in silos to be bagged for export.

Around 40% of Agricafe’s exports are vacuum-packed, a number that has continued to increase over the last four years. This is partly because the company has placed greater focus on more differentiated nano lots, but also because their market as become more demanding of quality. While this does create somewhat of a bottleneck, the end result is of such exceptional quality, that the Rodríguez family and their customers (ourselves included!) are willing to wait as long as it takes.