La Llama Gesha Coco Natural

Young mango, ripe strawberry and rock melon, with lingering jasmine florals. Distinct and pretty, with a syrupy texture.

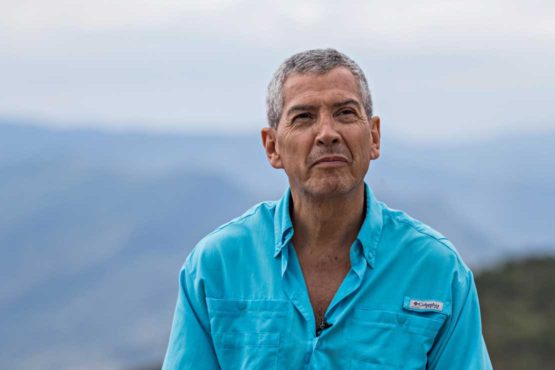

This Gesha nanolot comes comes from Finca La Llama, one of the latest additions to the Fincas Los Rodríguez farms. The farm is located in the colonia of Villa Rosario, which lies in a lush, steep mountain valley just outside of the town of Caranavi. The farm is owned by the Pedro Rodríguez and his family, who also operate the exporting business Agricafe Bolivia.

La Llama is the highest of all of the Los Rodríguez farms in Caranavi, sitting at over 1,700m above sea level. At this high elevation, temperatures are mild during the day and stable at night. This helps ensure a slow maturation of the cherry, which leads to an increased concentration of sugars in the cherry and bean, in turn producing a sweeter cup of coffee. Early in the morning or late afternoon, it is common to find an atmospheric fog covering the coffee plants, caused by the region’s unique microclimate. La Llama is 9.58 hectares in size, 5.24 of which are under coffee. While it had been producing coffee for over fifteen years when the family first acquired it, it has only been in harvest under their practices since 2017. Today, the farm’s production is still small, yet the Geshas produced here are of exceptional quality.

Reaching the highest point of the farm is an experience in itself. The trail to the top, which Pedro has affectionately dubbed “The Path of the Puma” (though no pumas are found on the farm!), begins at the rear of Las Alasitas farm, as shown in the video below – and as you travel along the winding, steep roads in a four-wheel-drive you’ll pass very neat and perfectly spaced rows of coffee. In the last couple of years, trees at La Llama have been spaced out further, to give the roots more room to expand, and to ensure branches can receive sunlight more directly. While this has reduced productivity of the plantation, it has reduced its need for irrigation, as water shortages are a major concern in the region.

Pedro and his family have invested a lot of time and effort into trying to make each of their plantations a ‘model’ farm that other producers in the area can learn from. Along with a focus on proper farming practices, the family have trialled several varieties at their farms in Caranavi. This particular lot is 100% Gesha – a variety renowned for its exceptional cup quality and distinct flavour profile. Gesha seeds were originally collected from Ethiopian coffee forests in the 1930s. They were initially kept and studied at the Tanzania Coffee Research Institute, and subsequently at Costa Rica’s Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza (known as CATIE). Both institutes recognised the variety’s resistance to coffee leaf rust, yet it was not propagated thoroughly due to the tree’s brittle branches. Luckily, in the 1960s, the variety was distributed to farmers in Panama by Francisco “Pachi” Serracin. Gesha trees made their way to the country’s Boquete region, where they grew at high elevations without attracting much attention from local farmers. It wasn’t until the Peterson family, in Boquete’s Hacienda La Esmeralda, noticed a number of trees that had not been affected by a recent bout of leaf rust on a newly-acquired plot of land, and decided to separate and cultivate them. The rest is history: the lot produced by these trees went on to win the Best of Panama competition in 2004, as its delicate, floral aroma and distinct flavour profile pushed the boundaries of what coffee could taste like.

In recent years, the Rodríguez have renewed their sustainability efforts across their farms. Because they understand that plants are supported by nutrients found in the soil, their practices have shifted to ensure these are constantly being replenished. This includes incorporating fallen leaves and coffee pulp on the bases of each tree, and planting shade trees (including eucalyptus trees and Flamboyanas, a species known locally as “fire flowers” because of their beautiful foliage) in areas with high risk of erosion. Not only have these practices improved Caranavi’s reddish, sandy clay soils, they have also helped boost its biodiversity.

All of the Rodríguez family’s learnings have also been shared with local producers through a training program that the family has developed called ‘Sol de la Mañana.’ Head here to learn more about this wonderful program, and here to learn more about the incredible work the Rodríguez family and Agricafe are doing in Bolivia.

ABOUT CARANAVI

The inhabitants of Caranavi first started farming coffee in the 1950s, when a government-led agrarian reform resulted in small parcels of land (of around 10 hectares in size each) being redistributed back to thousands of largely Aymara families. The Aymara are one of Bolivia’s 36 indigenous nations, who originally lived on the highlands of the Altiplano (a vast plateau of the central Andes that stretches from southern Peru to Bolivia and into northern Chile and Argentina). Along with the Quechuas, who lived in the Bolivian lowlands, both groups immigrated to Caranavi to find a better life through agriculture.

The municipality is located in the Yungas ecoregion, one of South America’s most fertile and diverse locations. The region runs along both sides of the Andes Mountains, and is known for the world’s highest lake, called Titicaca. In the Quechua language, Yungas translates to “the warm lands,” in reference to the rainy, yet warm climate experienced in the region.

HOW THIS COFFEE WAS PROCESSED

At La Llama, pickers from the Villa Rosario community and the state of Beni are hired to carefully handpick the coffee during the harvest. These pickers are hired by Elda and her husband Felix (Carmela Aduviri‘s son), and trained to collect only the very ripest cherries, and multiple passes are made through the farm throughout the harvest to ensure the coffee is picked at its prime. Selective picking is extremely important for special micro-lots like this one, to ensure the sweetest cup. The Rodríguez family has found that harvesting the very ripest (almost purple) cherries result in the most complexity and distinction in the coffee.

Pedro draws a lot of inspiration from the wine industry in his approach to coffee production, and is always innovating and trialling different processing techniques. This lot was processed with experimental techniques, part of the Rodriguez’ family’s long term strategy to achieve the greatest distinction and diversity in their special lots. As Pedro’s daughter, Daniela shares: “We’re keeping a registry of all the data we’re compiling, to use in the coming seasons. It includes information on the types of tanks used, bacteria and yeast activity, ambient temperature and weather conditions… we’re working hard to identify the ideal processing conditions for each variety and farm.” Watch the video below, to see how this coffee was processed:

Cherries for this lot were delivered to Agricafe’s state of the art mill Buena Vista in the evening. After being inspected and weighed, the coffee cherry was carefully sorted by weight using water, and floaters were removed. Following this, the coffee was placed a conveyor belt and disinfected, in a similar process used for wine grapes. It was then carefully washed and laid out to dry on patio for 48-72 hours, and then placed in one of Buena Vista’s ‘stationary box’ (or coco) dryers for up to 55 more hours, until it reached 11.5% humidity.

These boxes are series of steel containers that are typically used for drying cocoa pods. They use a gentle flow of warm air from below the coffee bed to dry the parchment slowly and evenly. Coffee was stirred manually at regular intervals to further ensure it dried at a uniform rate.

Once the coffee was dry, it was transported to La Paz where it was rested before being milled at Agricafe’s dry mill, La Luna. At this state-of-the-art mill, the coffee was first hulled and sorted using machinery, and then by a team of workers who meticulously sorted the coffee again (this time by hand) under UV and natural light. The mill is one of the cleanest and most impressive we have seen – you can read more about it here.